Introduction

Since the eruption of the volcano Eyjafjallajökull in 2010, Iceland has seen an incredible boom in tourism with growth rates unmatched anywhere else in Europe. Media coverage of the eruption brought increased awareness of the natural beauty of the remote nation which, when coupled with the severe decline in the Icelandic krona compared to other major currencies after the financial crisis, led to an unforeseen explosion in tourism of volcanic proportions. With the growth in hotels unable to keep pace with the record number of tourists visiting the country, Airbnb and similar companies have flourished. This article provides an overview of Iceland’s hotel market followed by a brief look at its sharing economy.Background

Given its remote location and small population of just 332,500, Iceland flew under the radar of the average traveller for many years. Only in the last five years or so has it crept towards the top of the to-do lists of more and more people. I myself visited for the first time in summer of this year, and was quick to sieze the opportunity to go back on business in September. Both times I found myself astounded by the friendliness of the locals, the sense of safety and the beauty of the countryside.Skogafoss, Southern Iceland

The range of different landscapes that can be traversed in a one-hour drive is incredible, from the volcanic, almost alien-like landscapes on the drive from the airport to Reykjavik; the greener-than-green pastures and plethora of waterfalls and ravines along the southern coast; to the restless geysers and haunting inland glaciers. It is not surprising that the country has become such a hot-spot for adventure travellers and nature lovers, just that it took so long to do so.

Iceland is between the Greenland Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean, to the northwest of the UK and Scandinavia. Covering an area of 102,820 km², Iceland’s landscape is volcanic, with more than 200 volcanoes, lava fields, hot springs and geysers. Additionally, one-tenth of its land mass is covered by ice caps. As a result of the challenging terrain, only the coastal lowlands are populated and cultivated. Despite its location and topography, Iceland’s climate is mild, moderated by southwesterly winds and the North Atlantic Drift, a powerful warm ocean current.

The Reykjanes Peninsula is in southwestern Iceland and is home to the country’s main international airport, Keflavik. The landscape of the peninsula, similar to the rest of Iceland, is rugged volcanic rock with little vegetation. Reykjanes lies along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates separate. Reykjavik, Iceland’s capital, is on the northern edge of the Reykjanes Peninsula. The city was founded in 1786, although it is believed that Viking settlements have existed in the same location since 870.

Map of Iceland

Market Overview

Economic Factors

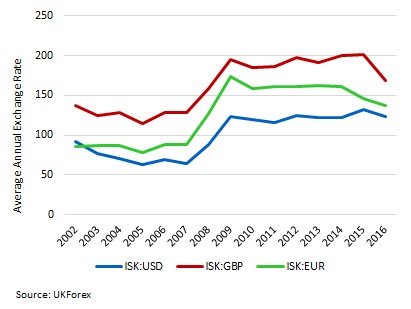

So what happened to bring so much attention to Iceland? The Eyjafjallajökull eruption in 2010 helped raise awareness of the country’s natural beauty, as did the increasing number of layovers at Keflavik International Airport for passengers travelling between the UK and the USA, but it was the sudden affordability following the strong depreciation of the currency that made the country so attractive to foreigners. The 2008 financial crisis hit Iceland particularly hard and ultimately resulted in the collapse of its banking sector, with all three of its major private banks going into default. This resulted in skyrocketing unemployment, political unrest and a rapid and severe devaluation of the Icelandic krona against other intenational currencies, as can be seen in the following graph.Figure 1: Icelandic Krona Exchange Rate with Major World Currencies

The exchange rate, which had been relatively stable at approximately 88:1 ISK:EUR in 2007, began to increase in early 2008 and by December of that year had peaked as high as 187:1 and remained almost as high for much of 2009. This led to soaring inflation, which in turn led to high interest rates, and the situation appeared desperate.

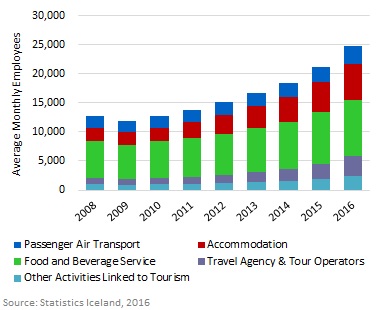

However, the new economic and exchange rate landscape made Iceland suddenly much more affordable to overseas visitors. The subsequent boom in tourism turned what looked to be years of high unemployment and a struggling economy into years of prosperous economic growth with near record-low unemployment levels. The following chart shows the growth of employment in tourism and related industries.

Figure 2: Average Number of Employees Working in Tourism and Related Industries

Of the different industries shown above, travel agency and tour operators grew the fastest with a compound annual growth rate of 17%, followed by accommodation at 13%. While food and beverage service still provides the largest number of jobs, other areas are becoming increasingly important.

Mount Esja as Seen from Reykjavik

Airport Statistics

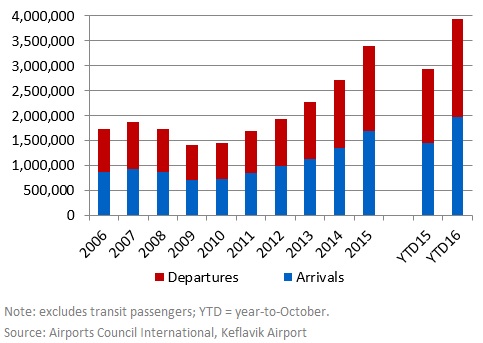

While increased awareness and favourable exchange rates were key for generating demand, the number of flights to and from the country was a major limiting factor. With the exception of the occassional cruise liner, virtually all visitors to Iceland must travel via Keflavik International Airport and, prior to 2010, only seven airlines offered scheduled flights to Iceland. According to a 2016 report titled ‘Tourism in Iceland’ by Islandsbanki, 25 airlines planned scheduled flights at some point in 2016. The increase in flights offered was the proverbial opening of the floodgates, as evidenced by the 40% increase in British tourists in 2012 when easyJet began scheduled flights ten months of the year, and the further 45% increase in British tourists when easyJet moved to year-round flights in 2013. Similar patterns were seen amongst German and American visitors owing to increased flights by Air Berlin, Delta Airlines, WOW and Icelandair. The following graph shows the evolution of passenger traffic at Keflavik International Airport since 2006. Figure 3: Passenger Movements at Keflavik International Airport 2006-15 and YTD

Since 2010, the Airport has recorded continuing double-figure growth; arrivals and departures grew by 16% in 2011, 19% in 2014 and almost 25% in 2015. Over year-to-October 2016, growth was a staggering 34% on the same period in 2015, and the total number of passengers in 2015 has already been surpassed. Although not included in the above table, the number of transit passengers through the airport has also increased exponentially. Between 2010 and 2015, transit passenger numbers grew at a compound annual rate of 35%, and by a further 45% in year-to-October 2016.

While this level of growth is unlikely to continue indefinitely, it is expected to do so for some time. However, infrastructure will be a major constraining factor. In its 2015-2040 Keflavik Airport masterplan, Isavia Ltd (the operator of Iceland’s airports) forecasts passenger demand to reach 14 million passengers per year by 2040 (including transit passengers). Over this time period, it has laid out a phased expansion plan that will increase the number of contact stands from 18 to 40 and add nine additional baggage claim belts. It also lays the framework for the addition of a third runway, but the timeline for this is not yet determined.

Supply

Despite the Capital Region only making up 1% of the total area of Iceland, it accounts for almost 50% of the room supply. The South has the second highest room capacity at 19% of the country's total, followed by the Northeast and East at 9% and 8%, respectively.Figure 4: Room Supply by Region (All Accommodation Categories)

.jpg)

In Reykjavik, hotels make up the vast majority of supply, at almost 80% of total guest rooms. Apartments and private homes are the second most common type of accommodation in the capital, yet only make up 10% of total room supply; guesthouses comprise 7% of rooms supply and hostels, 4%. In the country’s other regions, hotels are still the greatest source of room supply, but by a smaller margin compared to Reykjavik. In 2015, hotels accounted for just over 50% of the regional room supply.

Most hotel supply in Reykjavik is in the three- and four-star segments. Currently, there are no five-star hotels in the country, although trendy and lifestyle properties such as 101, Hotel Borg and Canopy by Hilton have opened in the last few years.

Overall, room supply grew at a compound annual rate of 11% between 2010 and 2015. In any other market this may have appeared to be somewhat alarming, but in Iceland it falls far below the the growth in demand, as seen in airport passenger growth and the visitation statistics in the following section.

In terms of proposed new supply, Iceland has an extensive pipeline that should be monitored closely by existing hoteliers. Estimates as to the number of rooms in the pipeline vary from 1,200 to over 2,000, with the majority of these rooms due in 2018 to 2019. Notable projects include two Curio Collection by Hilton hotels and the Rekjavik EDITION, which will be next to the Harpa Convention Centre and will be the country’s first five-star hotel.

Visitation

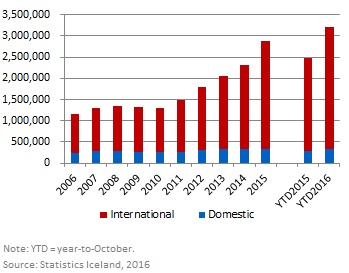

With the vast majority of visitors arriving by plane, the growth in total visitation closely mirrors that of airport passenger numbers.Figure 5: Accommodated Hotel Bednights in Iceland 2006-16

As with airport traffic, growth began to take off in 2011. Between 2010 and 2015, international bednights grew at the compound annual growth rate of 19%, with 2015 seeing a particularly strong increase of 29%. Year-to-October 2016 has seen similarly impressive growth, with the number of international bednights increasing by 31% on the same period 2015. While international demand is clearly driving the total growth, domestic demand has still achieved a respectable compound annual growth of 5% between 2010 and 2015, with a further 19% growth over year-to-October 2016.

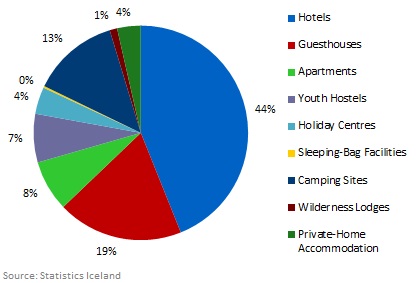

However, hotel bednights represent less than half of the total demand in Iceland. The following graph shows the distribution of bednights in the various categories of accommodation.

Figure 6: Accommodated Bednights by Type of Accommodation, 2015

Most of the accommodated bednights in Iceland are in hotels and guesthouses, followed by camping sites, apartments and youth hostels. With the exception of camping sites and wilderness lodges, all categories of accommodation saw double-figure annual demand growth between 2010 and 2015. Apartments and private-home accommodation were the fastest growing catagories, with compound annual growth rates between 2010 and 2015 of 30% and 34%, respectively.

Because a large portion of the hotels and guesthouses are in Reykjavik, the distribution of tourists in Iceland is highly concentrated in the Capital Region, where most visitors can use the city as a hub for visiting the surrounding countryside. Even if they do travel to other parts of Iceland for part of their trip, tourists will still typically stay for a night or two in Reykjavik. The following map shows the eight main regions in the country.

Regions of Iceland

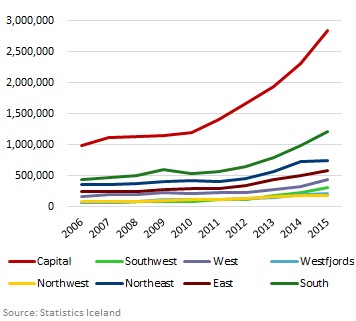

The following graph shows the trend in demand in each region. The exponential growth in the Capital Region is clearly visible, as is the increasing importance of the South. Although it only represents 5% of accommodated bednights, the Southwest (also known as the Southern Peninsula) is the fastest growing region, with a compound annual growth rate of 27% between 2010 and 2015.

Figure 7: Accommodated Bednights by Region

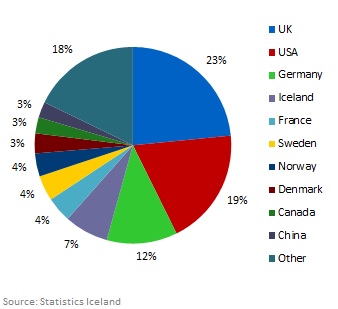

Having now looked at where tourists are going to, where are they coming from? Iceland is most reliant on the UK, the USA, and Germany. These are also extremely fast growing markets, with a compound annual growth rate between 2010 and 2015 of 31%, 39% and 18%, respectively. France and the Nordics are other important source markets, and visitors from Canada and China are growing at a rapid pace, as well.

Figure 8: Visitation by Source Country

While most of the source markets are generally stable and strong economies, such a heavy reliance on only three countries does pose some risk. This risk is well-illustrated by the changes in the UK economy seen in the few short months since the referendum. The Icelandic krona has appreciated in value over the last year. After Brexit, the pound dropped sharply against other currencies. These two factors combined has had a significant impact on the ISK:GBP exchange rate, making Iceland 30% more expensive for British travellers than it was at the beginning of 2015. Keeping in mind that the favourable exchange rate is what helped lead to the country’s tourism boom in the first place, this could have major implications on the amount of British visitors travelling to Iceland.

Landscape in Southern Iceland

Seasonality

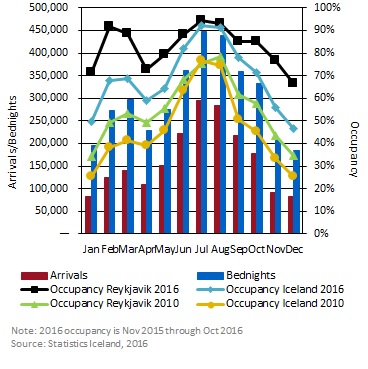

The following table provides an indication of seasonality in the Icelandic market in terms of arrivals, overnights and occupancy for the last year.Figure 9: Seasonality 2016 vs 2010

As can be seen in the 2010 occupancy levels in the above graph, Iceland as a whole was traditionally a highly seasonal market, with the summer months (June to August) being by far the busiest time of the year and the winter months (December to February) being the least busy. This is mirrored by the average daily hours of sunlight, which reach 22 hours in July and a low of just over two hours in December. Thanks to the warm Atlantic ocean currents, average monthly temperatures do not exhibit the same extremes, with average low temperatures in December just below freezing (-5 degrees) and peak summer temperatures of 15 degrees in July and August.

However, much has changed in the past six years. Demand throughout the year is far smoother than it was in 2010, although regional Iceland still has a pronounced peak in the summer. Reykjavik effectively has two peak seasons: the traditional June to August and, largely thanks to British travellers seeking the Northern Lights, a winter peak season of February and March. Occupancy levels rarely dip below 70% in the capital, with the weakest months of the year being January, December and, because the Northern Lights can no longer be seen and the warm long days of summer have not yet arrived, April.

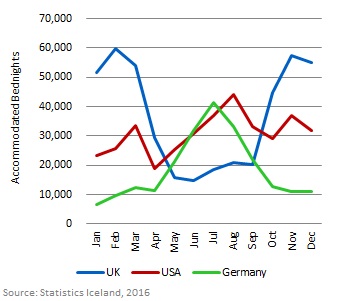

It is also worth noting that not all source markets share the same seasonality patterns. Focusing on the top three source markets, Germany and USA follow the more traditional seasonality with significantly more demand in the summer months, while UK visitors are the driving force behind the February and March peak season. The following graph shows the monthly number of accommodated bednights in hotels for the main source markets.

Figure 10: Seasonality of Main Source Markets

Although the diversity of seasonality patterns across the main source markets is on the whole beneficial for Iceland, it also highlights the risks associated with relying so heavily on a few markets. Visitation from the UK has been instrumental in smoothing demand throughout the year and creating the February to March peak season. If the rapid change in the krona to pound exchange rate over the last year does negatively impact British demand, this would likely hit the market harder than a similar drop in German or American visitors would, as hotels are virtually full in the summertime when Iceland is popular with all source markets, meaning demand would be less challenging to replace.

Hotel Performance

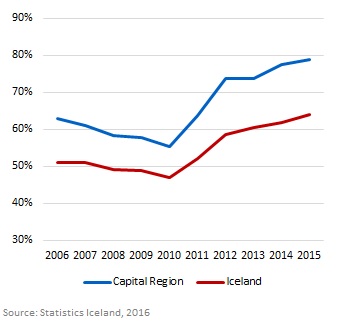

Prior to 2010, Iceland was a highly seasonal market and, as such, hotels struggled to achieve annual occupancies of just 50%. The recent boom in tourism has changed this, as can be seen in the following graph.Figure 11: Hotel Occupancy 2006-15

Between 2010 and 2012, hotel occupancies spiked sharply with the country seeing a 25% increase in occupancy levels and the Capital Region an even larger 33%. Occupancy levels have continued to increase since 2012, albeit at a slightly slower pace. This is due to the existing hotels having reached more or less full capacity during the peak seasons. Occupancy levels have also improved in the weaker months of the year, but at a slower rate.

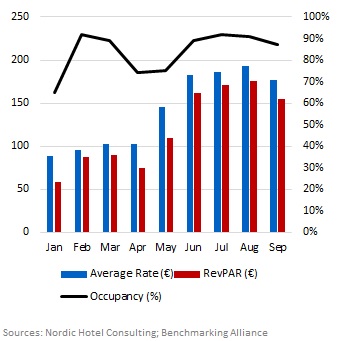

In terms of average rates, Reykjavik has performed strongly in 2016. In the first quarter rates increased by 8.3% on the same period in 2015, owing to a particularly strong February and March, which allowed for a 5.0% increase in RevPAR despite a slightly lower occupancy level. Quarter two was more stable with relatively flat average rate growth of only 0.2% and RevPAR growth of 1.0%, but the third quarter saw large increases in both occupancy and average rate of 6.3% and 8.4%, respectively. This contributed to quarter three RevPAR increase of 15.2% on the same period in 2015.

The year-to-September 2016 occupancy and rate dynamics are shown in the following graph.

Figure 12: Year-to-September 2016 Hotel Occupancy, Average Rate and Revpar

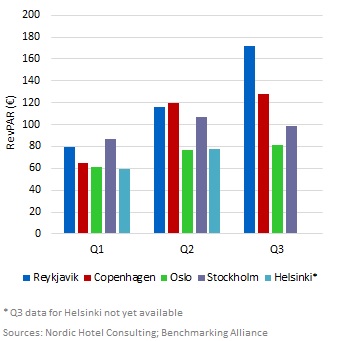

According to data provided by Nordic Hotel Consulting and Benchmarking Alliance, Reykjavik is fast becoming one of the strongest performing cities in the Nordics. Although its marketwide RevPAR was a close second to Stockholm in quarter one and Copenhagen in quarter two, Reykjavik had the highest occupancy in quarter one and strongest rate in quarter two. In quarter three 2016, Reykjavik’s performance far surpassed that of the other Nordic capitals. Owing to marketwide occupancy of 90% and an average rate of €190, RevPAR was 34% higher than the next-strongest city. A comparison of the RevPAR performance of the Nordic capitals is shown in the following graph.

Figure 13: Comparison of Nordic Revpar, 2016

Having now looked at the trends in demand and its impact on hotel performance, the following section will focus on Airbnb and the sharing economy, which has now become a major component of Iceland’s accommodation supply.

Sharing Economy

Although hotel room supply has grown by approximately 6% in Reykjavik annually since 2008, its growth has been far outstripped by that of demand. As such, alternative accommodation has seen phenomenal growth in Reykjavik. Determining the exact amount of alternative accommodation available has been difficult for the city, as a large number of listings on Airbnb and similar sharing economy sites are unregistered and occassionally less than legal. According to a report by Islandsbanki, the number of bednights sold through Airbnb equalled approximately 20% of sold hotel bednights. In the peak season, when the hotels in the city are essentially full and hotel rates are highest, listings through Airbnb were able to generate a third as many bednights as hotels.Despite the strong growth in bednights generated by Airbnb, hotel occupancy levels do not as of yet seem to be negatively affected. The sharing economy has mainly risen as a result of hotel supply being unable to keep up with the growth in demand and extremely high occupancy levels in peak seasons. However, hotels are still concerned by the rise of Airbnb for a number of reasons. First, it has created low-cost alternatives to hotels, which has limited the hotels' ability to drive average rates during the peak seasons. Second, there is a sense of unfairness about the situation felt by local hoteliers, as Airbnb-listed rental properties do not pay the same level of income or property taxes as the hotels, nor do they contribute to marketing the destination. Finally, although the sharing economy has risen mainly to supply demand that would otherwise be unaccommodated due to hotels being full, it is unclear what would happen if demand were to suddenly slow or decline. If hotels and private rentals were thrust into more direct competition, hotel occupancies and/or average rates could suffer.

It is not just the hotel market that has felt the pressure from Airbnb, either. The demand for income properties has risen dramatically due to the returns that can be achieved from renting on Airbnb, and house prices and long-term rents in central Reykjavik have risen sharply as a result. In an effort to better balance holiday rentals with the longer term needs of the local population, the government has passed a new law that will come into effect in January 2017. The new law states that a person can rent out their own accommodation and up to one other property owned by them for up to 90 days per year or until ISK2 million in gross rental income is reached. The law also aims to simplify the registration process and make it mandatory. Critics of the law suggest it is ambiguous, does not go far enough and will be difficult to enforce, but most agree it is a step in the right direction.

Fimmvörðuháls Hiking Trail, Southern Iceland

Going Forward

It should be clear from the statistics presented in this article that Iceland’s tourism industry has seen an exceptional transformation since 2010. Overnight stays almost tripled between 2008 and 2015, and 2016 has already surpassed last year’s levels. Although still a seasonal market, demand is much smoother throughout the year as an ever increasing number of tourists come in the winter to try to see the Northern Lights. Occupancy levels in the capital are near or above 90% for almost half of the year with respectable levels for the rest, and average rates were stronger than they were in all of the other Nordic Capitals in quarters two and three of 2016.The country is a land of opportunity, but as with any market that has seen such rapid changes, it is not without risk. The market relies heavily on leisure travellers, meaning a downturn in this segment would have a significant negative impact. Keflavik International Airport will need to expand to meet the growing passenger numbers, and failure to do so could hinder future growth. The appreciation of the Icelandic krona in the last year has made Iceland more expensive, particularly for British travellers who are also affected by the drop in the pound after Brexit. The 2017 February-March peak season should provide a good indication of the type of impact the disturbance in the exchange rate will have, as this is typically a key season for British tourists.

The explosion of the sharing economy combined with a hefty pipeline may also pose a threat to the hotel market. The current undersupply situation has allowed hotels and an extensive number of Airbnb listings to coexist peacefully, but once hotel room supply begins to catch up with demand, it will be an interesting case study to see whether hotels are able to reclaim the unaccommodated demand that had previously been forced into alternative accommodation when hotels were full.

Despite these risks, the potential for Reykjavik and the rest of Iceland is enormous. Friendly locals, a sense of safety and community, natural hot springs, towering waterfalls and the draw of the Northern Lights are just a few of the reasons why nature lovers and adventure travellers are flocking to Iceland, and hoteliers are sure to follow.

Northern Lights Above Reykjavik

0 Comments

Success

It will be displayed once approved by an administrator.

Thank you.

Error