Loosely speaking, revenue management (AKA “yield management”), a cornerstone of successful hotel operations, follows a formula: sell the right product to the right customer at the right time for the right price. Hoteliers accomplish this by effectively balancing occupancy and rate strategies to maximize revenue.

This article lays out the essential tenets and components of revenue-management practices, including how they relate to a hotel’s revenues and value.

A Brief History of Revenue Management

The concept and modern practice of revenue management originated in the 1970s when airlines began experimenting with new ways to fill seats without sacrificing ticket prices. To do this, they analyzed historical booking patterns of individual and subgroups of travelers. Two of the earliest approaches took the form of overbooking flights and offering discounts to passengers who book early.

Overbooking worked on the principle of predicting the number of passengers who would not show up for a specific flight and selling those seats again to new passengers. Airlines would analyze historical data for similar flights, looking specifically at how many ticketed passengers did not arrive, and overbook by the same number. This practice all but guaranteed that all seats would be filled on a given flight.

To maximize potential revenue further, airlines also began to change ticket prices throughout the booking cycle and gauge corresponding demand levels. Airlines would allocate a number of seats three or more months from the departure date at a lower ticket price, typically appealing to the leisure traveler to provide a base of business for a specific flight. As the departure date approached, airlines would increase rates to maximize yield, knowing most of these last-minute travelers (often commercial customers for whom the travel was necessary and inflexible), would pay the higher price.

Hoteliers Adopt the Trend

These practices became known as “yield management,” and hoteliers did not take long to adopt them. The move made sense for hotels, which also looked to maximize revenues with a pricing strategy based on historical consumer purchasing analytics and demand trends. In the late 1980s, larger hospitality companies implemented similar strategies, and Sheryl E. Kimes’ oft-cited paper, “The Basics of Yield Management,” appeared in the Cornell Quarterly in November 1989.

Today, revenue-management strategies are woven into the very fabric of successful hotel operations, and they continue to evolve.

Hotel Revenue Management

For hotels, revenue management varies by asset type, location, brand, management, and ownership. Strategies, however, tend to focus on two segments of demand: transient and group. These two segments serve as the foundation for the pricing and mix of business at a particular hotel. Hoteliers must understand each, as well as how they work together, to develop an effective pricing strategy for a hotel.

Transient Business

Transient pricing strategies are designed for individual guests staying at a hotel, whether for business or for pleasure. Essentially, transient guests are not affiliated with a group booking or a contract block agreement. This section presents a basic approach to maximizing transient revenues, including effective pricing, segment pricing strategies, inventory management, and forecasting.

Technology, Pricing, and Guest Satisfaction

Optimized, time-sensitive, and customer-targeted pricing strategies for hotel rooms are typically arrived at in one of two ways (or a combination of both). The first simply relies on experienced managers or management teams, who price rooms based on their knowledge of competitive products and pricing, as well as their property’s historical and forward-looking trends. These managers now have access to competitor rates through several sources that allow them to “shop” competitor rates by searching published online travel agency (OTA) rates automatically.

A strategy coming more into wide-scale use is to set pricing with the help of sophisticated software and revenue-management systems developed by hotel brands, management companies, and outside consultants. Today’s top hotel companies invest heavily in software that aids revenue-management decisions. Examples include HiltonGro (Hilton), One Yield (Marriott), and IDeaS and Duetto, which are independent systems used by many hotel franchises and independent hotels. The playing field has been leveled somewhat between branded and independent hotels related to access to these high-tech systems. The upfront cost of these systems was in the $30,000 to $50,000 range until about four years ago, a prohibitive cost for most independent hotels and small boutique hotels in particular, even given the higher average rates at such properties. With the advent of cloud-based systems and increased competition, these new high-tech systems can be acquired for an upfront cost of between $7,000 and $10,000, with monthly fees now between $6 and $10 per available room per month.

Both methods rely heavily on evaluating the historical performance of a specific hotel, forecasted demand and occupancy, and vigilant monitoring of competitor pricing. The benefits of going high-tech include the ability to gather and monitor mass amounts of complex data on demand in real time, so that managers can accordingly adjust pricing strategies based on market conditions and competitive moves.

These revenue-management systems “learn” and provide suggested rates based on their analysis that no human can replicate. The technology cannot, however, be left untended, and even the most sophisticated systems and algorithms do not replace a revenue manager’s ability to gauge forces in the market that can affect pricing. These factors include the state of the local, regional, national, and global economies; demand and pricing levels induced by non-recurring special events; and general knowledge of market dynamics.

Mark Lynn, head of HVS’s Asset Management & Advisory group in San Francisco, notes that, despite the vital data it produces, “the use of technology alone is a short-sighted approach. There are always unique circumstances occurring in a hotel’s competitive environment that may not show up in the numbers.”

Lynn argues that hotels must provide “price value” to guests, something that can be sabotaged by strict reliance on technology. “We have seen situations where the technology dictates the setting of outrageous rates based on high demand.” While guests may be forced to book one time, he says, they leave feeling coerced, and are unlikely to return. “There has to be a balance of logic and guest satisfaction injected into the rate-setting process,” Lynn says.

Pricing Strategies Suited to Demand

The level of support in setting room rates differs with a hotel’s product type, location, and brand. Management teams review and adjust rates daily—often frequently throughout the day—and make tactical decisions on rates over the next 90 days. It is extremely important to have longer-term strategic pricing guidelines in place that are determined annually in strategy meetings with hotel leadership. These long-term rate strategies serve as a basis for adjusting rates during shorter-term tactical initiatives.

Typically, hotel management will employ one of the two following strategies to price rooms. The first is a “weekday versus weekend” strategy, with one guestroom rate for Sunday through Thursday and another for Friday and Saturday. Another approach is known as the “dynamic” pricing strategy. Used to maximize pricing during the highest levels of occupancy, the dynamic approach also allows the flexibility of offering lower guestroom rates on shoulder nights around peak occupancy days, as well as on weekends.

Hoteliers will also home in on pricing for specific segments of transient demand, including commercial, leisure, government, and extended stay. Examples of pricing strategies specific to these segments are listed below.

Special Corporate Pricing: Commercial guests, defined as those traveling on business, will frequently book within a shorter period, and typically have a larger budget for travel. Larger companies will often negotiate for special rates given the high levels of business they produce for a hotel. These negotiated room rates may be offered locally or across multiple properties nationally and help establish a strong occupancy base for hotels. In markets with limited corporate demand, hotels will often offer one commercial rate for business travelers.

Leisure Packages and Advance Bookings: Leisure demand designates hotel guests traveling on vacation, visiting friends or family, and for other reasons not associated with a business purpose. These guests are characterized as price-sensitive travelers, prone to search for the best deal. Hotel management will offer a variety of special rates and packages designed to add value for leisure guests. These packages may include free amenities such as breakfast at the hotel or tickets to a show or other local attractions. Another pricing tool is known as the “advanced purchase rate.” This discounted rate normally requires an advance reservation with a full, usually non-refundable deposit, appealing to leisure guests with definite travel plans made well ahead of the date of travel.

Contract Agreements: Contract agreements are designed for industries that need a constant supply of guestrooms. For hotels located near an airport or a major seaport, for example, contract agreements with airlines or cruise ships can be an effective pricing strategy. Hotels with a large supply of guestrooms often benefit from these agreements, which can provide a foundation for consistent occupancy. It is important to note, however, that these agreements are often secured at lower rates given the large quantity of room nights provided throughout the year.

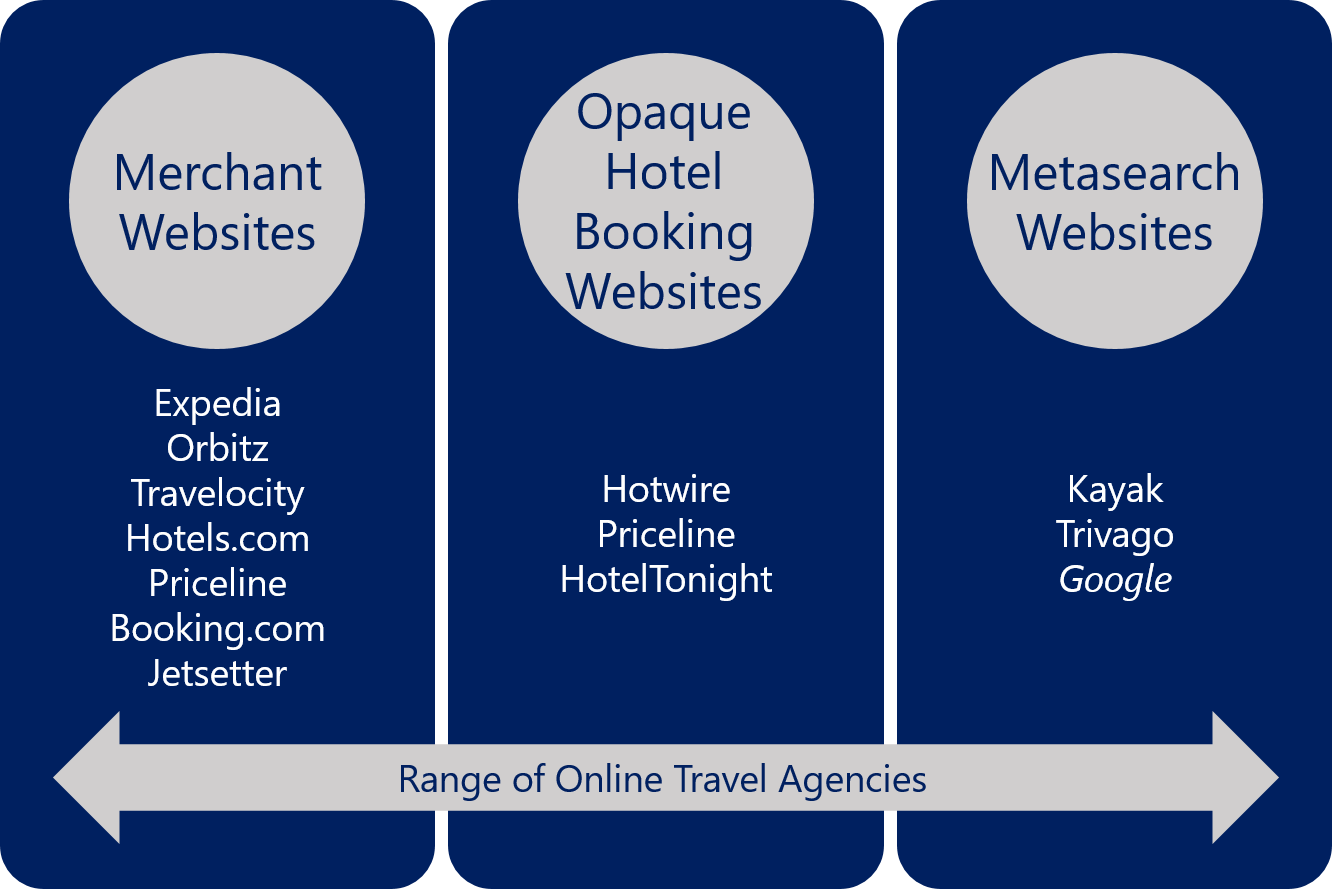

Third-Party Booking Agencies and Online Travel Agencies: Third-party booking agencies and online travel agencies (OTAs) allow guests to book hotel rooms, along with flights, rental cars, and other travel conveniences, online. These entities typically operate in one of three ways.

“Merchant” websites (e.g., Expedia, Orbitz) offer guestrooms for a given date from hotels in a market, and guests can search among selected hotels by name. Merchant sites then receive a commission for each guestroom booked. Independent hotels can limit the number of rooms allotted to the merchant sites on any given day, but most branded hotels cannot.

“Opaque” hotel booking websites (e.g., Hotwire, Priceline), by contrast, offer guestrooms by rate, without identifying the hotel by name until after a guest has chosen and finished the booking. Opaque sites allow hotels to offer deeper discounts without violating rate-parity agreements, which compel hotels to offer consistent pricing across the brand.

Beyond these, there are “metasearch” websites (e.g., Kayak) that provide a “one-stop-shop” listing of hotel room rates, directing guests to either a hotel’s website or a third-party website for booking (whichever has the lowest rate or best meets the search criteria).

The graphic below provide some examples of each type of company, as well as some pros and cons of each from the perspective of hoteliers regarding third-party sites as a whole.

Range of Online Travel Agencies (Merchant, Opaque, and Metasearch)

Pros and Cons of OTAs Range from Expanding a Hotel’s Exposure to Lower Profits

Direct Bookings: Direct bookings through brand-managed websites have become increasingly popular at hotels, which offer special rates and conveniences to guests who book directly. Common offers include complimentary wireless Internet, a percentage discount, a complimentary room upgrade, late checkout, or other incentives. Direct bookings and associated rewards also help increase brand loyalty, as well as freeing the hotel from commissionable payments to third parties and the reduced risk of rate parity.

Hotel companies have continued to promote direct bookings with advertisements and appeals to frequent traveler members. Major hotel brands including Marriott, Hilton, Hyatt, InterContinental Hotels Group, Wyndham, and Choice have begun to aggressively encourage direct bookings at company hotels. The discounts offered by the brands are now a direct challenge to the OTAs and provide owners with the ability to increase the average rates they would receive from the OTAs.

Inventory Management

In addition to determining pricing strategies for transient guests, revenue management involves management of the hotel’s physical inventory of guestrooms. Revenue managers maintain inventory through “straight-line availability,” that is, a process of ensuring that all guestroom types are available at all times. This allows guests to continue booking specific room types, as well as long-term stays, by ensuring a certain number of each type of room is available each day. Revenue managers must also  recognize when certain room types should not be made available, such as on high-occupancy days. This allows higher-rated rooms to sell, maximizing revenue.

recognize when certain room types should not be made available, such as on high-occupancy days. This allows higher-rated rooms to sell, maximizing revenue.

Some hotel companies now have revenue-management systems that help manage inventory, as well as pricing, by forecasting demand by room type and occupancy. Inventory management is especially crucial and complex during a property renovation, when a selection of the hotel’s rooms is out of inventory.

Forecasting

Hotel management relies on accurate occupancy forecasts for the basis of hotel operation, including all staffing, supplies, and food and beverage needs. These forecasts influence minor and major decisions aimed at running a hotel as efficiently as possible. Similar to pricing, a hotel’s occupancy forecasts are made continually and based on reviews of historical data and current trends.

The newest sophisticated revenue-management systems forecast by market segment so that rates per different channels and sources can be adjusted to maximize revenue. For example, revenue managers will compare the hotel’s year-over-year occupancy levels to gauge where bookings stand for specific timeframes. Management will also evaluate the more recent trends, such as the current guest-booking window and the 90-day room-night trends.

While historical information helps guide the process of pricing and inventory management, a view on current trends is essential to gauge changes in the market (such as new supply and economic factors), as well as guest preferences and buying behaviors.

Meeting and Group Business

Meeting and group demand capture forms the second half of a hotel’s revenue-management strategy. Groups normally need a block of at least ten guestrooms over a defined timeframe and may require meeting space, as well. These groups can include commercial or leisure guests and can book anywhere from 30 days to several years prior to their dates of stay, depending on the size and scale of the group and/or meeting.

The following presents some considerations for an effective meeting and group revenue-management strategy.

Group Ceiling

A hotel’s “group ceiling” refers to the maximum number of rooms dedicated to group blocks for any given day of the week. This ceiling is defined, essentially, by how many rooms need to remain in inventory to maximize full revenue potential with transient segments. This can vary by season, market, and type of hotel. Hotels with fewer guestrooms relative to those in their competitive set should be more selective with their group bookings and careful not to displace more higher-rated business, while larger hotels have more flexibility.

Meeting Space

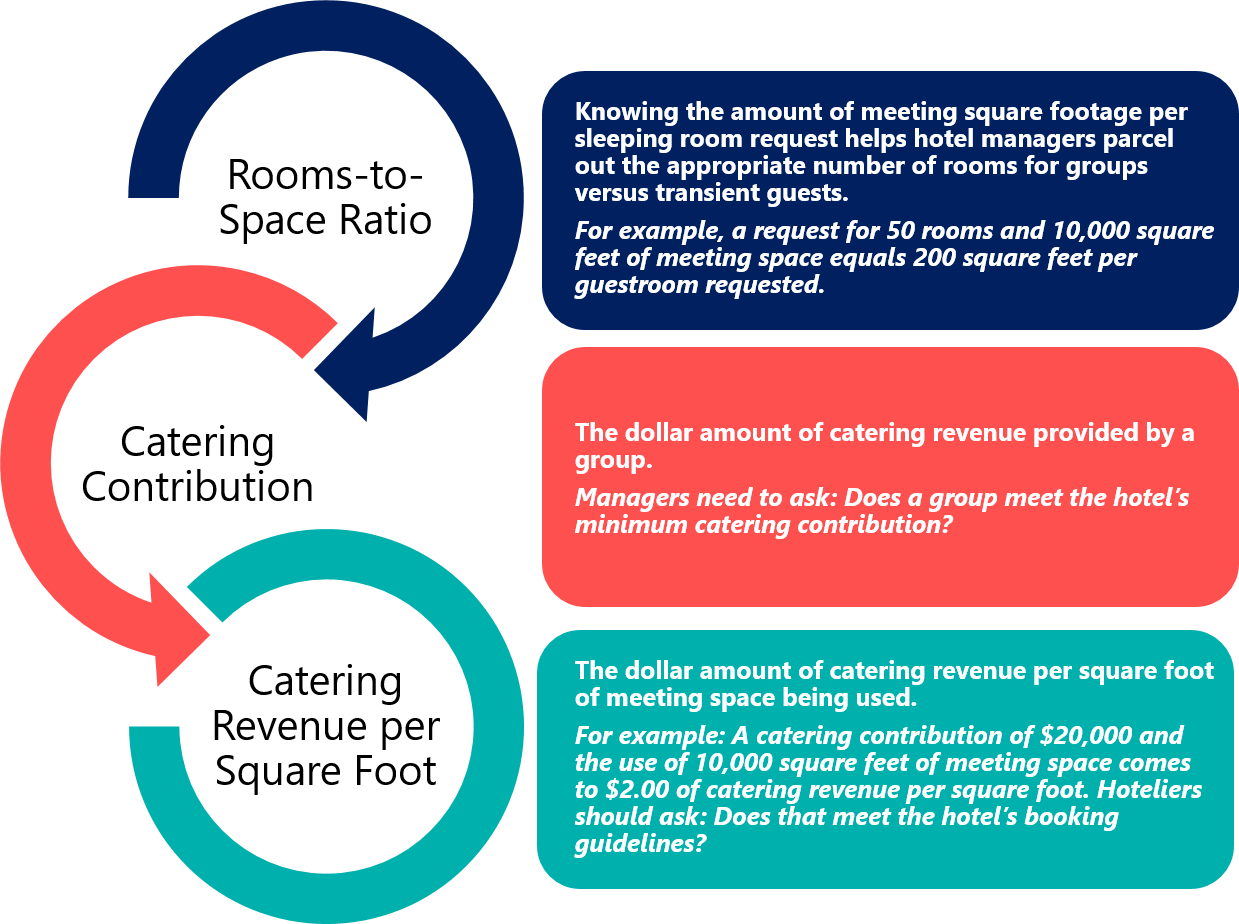

Revenue managers need to evaluate if and how much meeting space is needed when booking groups. Considerations for evaluating a group’s meeting space needs include:

These considerations help determine whether and to what extent group bookings align with the overall revenue-management strategy at a hotel. They also apply to determining whether a hotel can maximize revenue.

Displacement

Displacement refers to the amount of business being displaced by booking meetings and groups at a hotel. Managers begin to gauge displacement based on an evaluation of demand from this segment in the current year versus the one prior, including which groups have been confirmed, which are tentative, and which are prospective. This is then compared against projected transient room-night demand and rates over the same timeframe, as well as local events that may produce spikes in demand.

Hotel managers use a series of questions to evaluate the positive and negative impacts of group bookings, including how and to what extent meeting and group business may result in displacement. These include:

- How much revenue will a meeting or group booking create for the hotel in the form of room nights, food and beverage, and/or meeting space rental?

- Does the meeting or group booking threaten to displace higher-rated transient business?

- Could taking smaller groups at a higher rate sell out the hotel in other segments?

- Is the group a rooming list or a call-in?

- Will the group sign a contract with attrition for rooms not occupied?

- Does the group have a history at the hotel (or at another hotel) from which data can be drawn and evaluated?

The range of such questions will depend on a hotel’s size, service level, and attributes of its market. However, focused inquiries of this type are essential to maximizing revenues when bidding for group business.

Citywide Events

In metro markets with large, dedicated convention facilities, demand capture from “citywide” conventions becomes a central component to maximizing hotel revenue. The biggest citywide events, such as the Super Bowl or the Global Consumer Electronics Tradeshow in Las Vegas, can create enough demand to saturate local hotels and even expand to surrounding markets. The influx of demand from these kinds of events also allows hotels to command much higher room rates and capture definite lengths of stay.

Smaller-scale, lower-rated citywide conventions and events can also generate significant demand; moreover, hotels can command higher rates through guests booking outside of a prearranged citywide group block or through transient guests booking at the same time as but not affiliated with the convention/event.

Revenue Management and Hotel Valuation

Because they have so much to do with a hotel’s profits and operational efficiency, revenue-management strategies ultimately play into a hotel’s value. Although a valuation does not include an explicit assessment of a hotel’s revenue-management strategy, some knowledge of a hotel’s successes and challenges in this regard is inherent to a comprehensive appraisal.

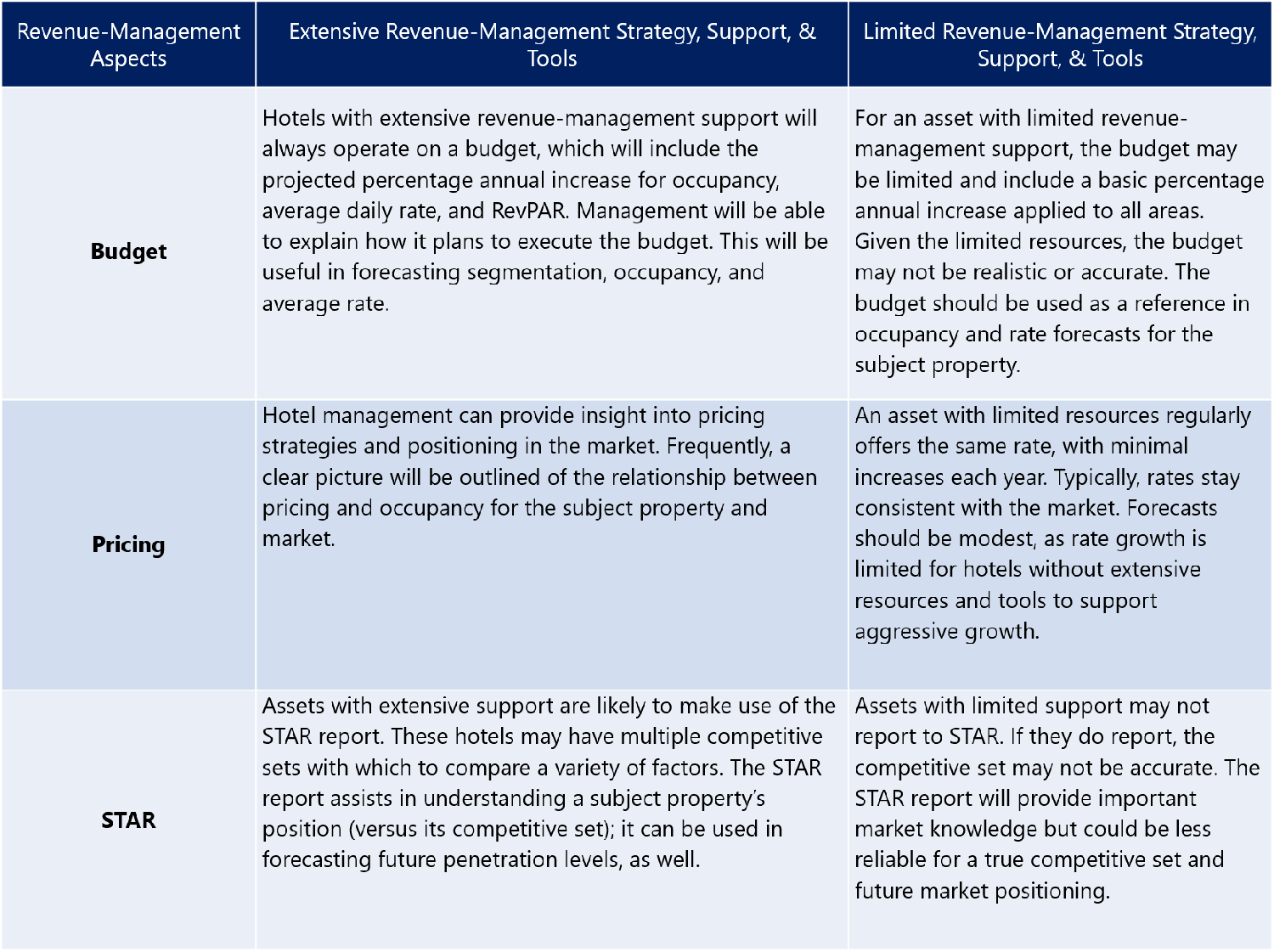

The following chart examines how two revenue-management strategies, one extensive and the other more limited, give an appraiser a more thorough understanding of a hotel’s operation.

Conclusion

Over the course of its evolution since the 1970s, revenue management has continued to challenge and reward hoteliers. Effective revenue-management strategies have become more complex in the age of fast-moving technological innovations, and software-based strategies that gather and draw from wide-ranging datasets have become the norm for hotel brands.

The importance of an experienced management team, however, cannot be displaced when it comes to using data to hone a revenue-management strategy focused on transient versus meeting and group business at a hotel. Overall, efficient hotel operations depend on revenue managers keyed in to all elements of a hotel’s dynamics, including rates, occupancy, demand, and competition. The right blend of smart technology, experienced managers, and well-honed strategies, in the end, forms the basis of successful revenue management for any hotel.

excellent and good tools

Very Informative and